A typical example involves designing and constructing a small-scale bridge using limited materials, applying principles of statics, mechanics, and material science to maximize load-bearing capacity. Students often explore concepts such as tension, compression, shear, and torque, translating theoretical knowledge into practical engineering solutions. Variations might involve specific material constraints, bridge type limitations (beam, truss, arch, suspension), or scale modeling of real-world structures.

Such activities offer valuable educational experiences, fostering problem-solving skills, promoting teamwork, and demonstrating the practical applications of physics. They provide a tangible connection between abstract concepts and real-world engineering challenges, cultivating a deeper understanding of structural design. Historically, bridge building competitions have served as a platform to identify and nurture engineering talent, reflecting the enduring importance of infrastructure in societal development.

Further exploration might consider the evolution of bridge design principles, advancements in materials science relevant to bridge construction, or the role of computer-aided design in modern engineering projects. An examination of specific bridge failures and the lessons learned can also offer invaluable insights into the crucial interplay of physics and engineering.

Tips for Successful Structural Design Projects

Careful planning and execution are crucial for achieving optimal results in structural design projects. The following tips offer guidance for maximizing load-bearing capacity and ensuring structural integrity.

Tip 1: Accurate Material Selection: Thorough material research is essential. Consider properties such as Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and density. Balsa wood, for example, offers a high strength-to-weight ratio, making it a popular choice.

Tip 2: Efficient Load Distribution: Distribute applied forces evenly across the structure. Truss designs, employing interconnected triangles, effectively distribute loads and enhance stability.

Tip 3: Optimization of Structural Geometry: Geometric shapes significantly influence a structure’s ability to withstand stress. Arches, for instance, effectively transfer loads into compressive forces, contributing to stability.

Tip 4: Minimize Material Usage: While ensuring structural integrity, minimize unnecessary material to reduce overall weight. Strategic placement of reinforcing elements can achieve this balance.

Tip 5: Prototyping and Testing: Iterative prototyping and testing are invaluable for identifying weaknesses and refining the design. Scale models allow for controlled experimentation and optimization.

Tip 6: Consider Environmental Factors: Account for potential environmental influences such as wind resistance or temperature fluctuations, especially when scaling to real-world applications.

Tip 7: Documentation and Analysis: Meticulous record-keeping of design choices, calculations, and test results facilitates understanding and future improvements.

Adhering to these principles will not only increase the likelihood of project success but also provide valuable insights into the complexities of structural engineering.

By integrating these considerations, projects can move from theoretical concepts to practical, efficient, and robust structural solutions.

1. Design

Design constitutes the foundational stage of a physics bridge project, directly influencing its ultimate success. A well-considered design accounts for factors such as anticipated load, material properties, and structural principles. Cause and effect relationships are paramount; design choices directly impact the bridge’s ability to withstand stress. For example, a truss design, employing interconnected triangles, distributes load more effectively than a simple beam design, resulting in a higher load-bearing capacity. Careful consideration of member placement and angles within the truss further optimizes load distribution and overall structural integrity. A thorough design process anticipates potential points of failure and incorporates solutions proactively.

Real-world examples illustrate the critical role of design. The collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940 highlighted the devastating consequences of neglecting aerodynamic stability in the design phase. Modern bridge design incorporates extensive wind tunnel testing and computational fluid dynamics analysis, directly addressing this historical lesson. Conversely, the Akashi Kaiky Bridge, with its innovative suspension design, exemplifies successful integration of advanced engineering principles to withstand extreme environmental conditions. These examples underscore the practical significance of a robust design process in ensuring structural longevity and safety.

In conclusion, the design phase serves as the blueprint for a successful physics bridge project. A comprehensive design process, informed by physics principles and real-world case studies, mitigates potential failures and paves the way for efficient and robust structural solutions. Challenges often arise in balancing design complexity with material constraints and construction feasibility. Overcoming these challenges through iterative design refinement and rigorous analysis strengthens understanding of structural mechanics and underscores the crucial link between theory and practice in engineering.

2. Construction

Construction represents the critical transition from theoretical design to physical realization in a physics bridge project. This phase directly influences the final structure’s performance and embodies the practical application of design principles. The construction process inherently involves a series of choices, each with consequential effects on structural integrity. Precise material cutting and assembly, for instance, directly affect load distribution and the bridge’s ability to withstand stress. A seemingly minor misalignment during construction can amplify under load, potentially leading to premature failure. Conversely, meticulous attention to detail during construction maximizes the intended design’s effectiveness.

Real-world bridge construction offers valuable parallels. The Millau Viaduct, renowned for its towering piers and graceful cable-stayed design, exemplifies the complex interplay of engineering and construction. Its construction required innovative techniques to overcome logistical and environmental challenges, demonstrating the crucial role of adaptable construction methods in realizing ambitious designs. Conversely, instances of bridge collapses often trace back to construction errors, such as faulty welding or improper material handling, highlighting the severe consequences of deviations from established construction practices. These examples underscore the critical link between precise construction and structural performance.

In summary, the construction phase translates design blueprints into tangible structures. Challenges often arise in reconciling design ideals with the practical limitations of available materials and construction techniques. Successfully navigating these challenges requires meticulous execution, continuous quality control, and a deep understanding of the cause-and-effect relationship between construction techniques and structural performance. A well-executed construction process maximizes the effectiveness of the initial design, ensuring that the final bridge reflects the intended structural integrity and load-bearing capacity. This stage ultimately determines the project’s success in demonstrating the practical application of physics principles to real-world engineering challenges.

3. Material Selection

Material selection stands as a pivotal factor in physics bridge projects, directly influencing structural performance and reflecting core physics principles. The inherent properties of chosen materials govern a bridge’s ability to withstand applied loads. Material characteristics such as Young’s modulus (a measure of stiffness), tensile strength (resistance to pulling forces), and compressive strength (resistance to pushing forces) directly dictate load-bearing capacity. Cause and effect relationships are evident: choosing a material with high tensile strength but low compressive strength, for example, might lead to failure under compression. Hence, material selection acts as a tangible link between abstract physics concepts and practical engineering outcomes. Selecting balsa wood for its high strength-to-weight ratio exemplifies a strategic choice based on material properties relevant to bridge design.

Real-world bridge construction underscores the critical nature of material selection. The Forth Bridge, a cantilever railway bridge, utilizes steel for its high tensile strength and durability, enabling its impressive span. Conversely, the use of reinforced concrete, combining concrete’s compressive strength with steel’s tensile strength, allows for versatile and cost-effective bridge designs. The choice of materials often involves trade-offs. Steel offers strength but is susceptible to corrosion; concrete provides durability but is heavier. Furthermore, advancements in material science continuously introduce new possibilities, such as fiber-reinforced polymers, which offer high strength-to-weight ratios and corrosion resistance, opening new avenues for innovative bridge designs.

In conclusion, material selection represents a critical juncture in physics bridge projects, bridging theoretical understanding with practical application. Choosing appropriate materials requires careful consideration of their inherent properties, load requirements, and environmental factors. Challenges frequently arise in balancing desired material properties with cost and availability. Overcoming these challenges requires informed decision-making based on a deep understanding of material science and structural mechanics. Ultimately, successful material selection ensures the bridge’s ability to withstand intended loads, reflecting a comprehensive understanding of physics principles and their translation into real-world engineering solutions.

4. Testing

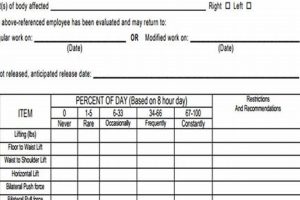

Testing constitutes a crucial stage in any physics bridge project, providing empirical validation of design choices and theoretical calculations. This process involves subjecting the constructed bridge to controlled loads, meticulously measuring its response to stress, strain, and deflection. Cause and effect are directly observed: applied loads produce measurable effects on the structure, offering insights into load distribution, structural weaknesses, and ultimate load-bearing capacity. Testing reveals whether the bridge behaves as predicted by physics principles and design calculations. A bridge exhibiting unexpected deflection under load, for example, indicates a potential flaw in design or construction, prompting further investigation and refinement.

Real-world bridge testing procedures underscore the importance of this stage. Load testing, often involving strategically placed weights or hydraulic jacks, simulates real-world traffic conditions to assess bridge integrity. Non-destructive testing methods, such as ultrasonic inspection and strain gauge measurements, provide detailed insights into structural behavior without causing damage. The lessons learned from bridge failures, such as the Silver Bridge collapse in 1967, highlight the catastrophic consequences of inadequate testing and inspection. Modern bridge management practices incorporate rigorous testing protocols throughout a bridge’s lifecycle, ensuring ongoing structural integrity and public safety. These real-world examples demonstrate the practical significance of comprehensive testing in verifying structural performance and preventing potential disasters.

In conclusion, testing serves as an indispensable component of physics bridge projects, providing crucial feedback on design effectiveness and construction quality. Challenges often arise in replicating real-world loading conditions and accurately measuring structural responses. Addressing these challenges requires careful experimental design, precise instrumentation, and rigorous data analysis. The insights gained from testing inform future design iterations, strengthen understanding of structural behavior, and ultimately contribute to the development of safer and more efficient bridge designs. This stage bridges the gap between theoretical predictions and practical performance, demonstrating the essential role of empirical validation in engineering design.

5. Analysis

Analysis forms the crucial link between theoretical understanding and practical outcomes in a physics bridge project. This stage involves scrutinizing data collected during testing, applying physics principles to interpret structural behavior, and drawing meaningful conclusions about design effectiveness and structural integrity. Cause and effect relationships are rigorously examined: observed deflections, stresses, and strains are directly linked to design choices, material properties, and construction techniques. Analysis reveals whether the bridge performs as predicted, identifies potential weaknesses, and provides valuable insights for future improvements. For instance, analyzing the distribution of stress across different members of a truss bridge can reveal areas of overstress or underutilization, informing design optimization for subsequent iterations. This analytical process strengthens understanding of fundamental physics concepts, such as force distribution, stress-strain relationships, and material behavior under load.

Real-world bridge failures often prompt extensive analysis to determine the root causes and prevent future occurrences. The Hyatt Regency walkway collapse in 1981, for example, led to detailed structural analysis, revealing critical design flaws and underscoring the importance of rigorous analysis in ensuring structural safety. Conversely, the successful design and construction of iconic bridges like the Golden Gate Bridge rely heavily on sophisticated analysis techniques, including finite element analysis, to predict structural behavior under various loading conditions and environmental factors. These examples demonstrate the practical significance of thorough analysis in both learning from past failures and ensuring the success of future bridge projects. They highlight the role of analysis in bridging the gap between theoretical models and real-world performance.

In conclusion, analysis represents the intellectual culmination of a physics bridge project, translating empirical observations into actionable insights. Challenges often arise in accurately modeling complex structural behavior and interpreting data from diverse sources. Overcoming these challenges requires proficiency in physics principles, engineering analysis techniques, and critical thinking. The insights derived from analysis not only validate design choices and construction methods but also deepen understanding of structural mechanics and inform the development of more efficient and resilient bridge designs. This stage solidifies the connection between theoretical knowledge and practical application, demonstrating the essential role of analysis in advancing engineering design and ensuring structural safety.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding structural design projects, focusing on practical considerations and underlying physics principles.

Question 1: How does the choice of bridge type (beam, truss, arch, suspension) influence load-bearing capacity?

Different bridge types distribute loads in distinct ways. Beam bridges rely on material strength to resist bending. Truss bridges utilize interconnected triangles to distribute loads efficiently. Arch bridges transfer loads into compressive forces along the arch. Suspension bridges utilize cables and towers to support the deck. The optimal choice depends on span length, material properties, and load requirements.

Question 2: What is the significance of the strength-to-weight ratio in bridge design?

A high strength-to-weight ratio signifies that a material offers significant strength for a given weight. This is crucial in bridge design as it minimizes the bridge’s self-weight, allowing it to support a greater external load. Materials like balsa wood and carbon fiber composites are prized for their high strength-to-weight ratios.

Question 3: How do environmental factors, such as wind, affect bridge design?

Wind loads can impose significant stresses on bridges. Design considerations must account for potential wind forces, including aerodynamic stability to prevent oscillations. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse exemplifies the devastating consequences of neglecting wind effects. Modern bridge designs incorporate wind tunnel testing and computational fluid dynamics analysis to mitigate wind-related risks.

Question 4: What role does computer-aided design (CAD) play in modern bridge engineering?

CAD software allows engineers to create detailed 3D models, perform structural analysis, and simulate various loading scenarios. This facilitates design optimization, identifies potential weaknesses before construction, and enables efficient communication among project stakeholders.

Question 5: How do material properties influence bridge longevity and maintenance requirements?

Material properties such as corrosion resistance, fatigue resistance, and durability directly impact a bridge’s lifespan and maintenance needs. Steel, while strong, requires corrosion protection. Concrete offers durability but can crack under stress. Material selection must balance initial cost with long-term maintenance expenses.

Question 6: What are some common failure modes in bridges, and how can they be prevented?

Common failure modes include buckling, fatigue cracking, and connection failures. Buckling occurs when compressive forces exceed a member’s capacity. Fatigue cracking results from repeated stress cycles. Connection failures compromise the integrity of joints between bridge components. Proper design, material selection, construction quality, and regular inspection mitigate these risks.

Understanding these fundamental aspects of structural design contributes to safer, more efficient, and durable bridge construction.

Further exploration might delve into specific case studies of bridge successes and failures, providing valuable context for these principles.

Conclusion

A physics bridge project encapsulates fundamental principles of structural mechanics, material science, and engineering design. Exploration of design, construction, material selection, testing, and analysis reveals the intricate interplay of these disciplines. Successful execution necessitates a comprehensive understanding of load distribution, stress-strain relationships, and material properties. Furthermore, consideration of real-world constraints, such as environmental factors and material availability, underscores the practical challenges inherent in translating theoretical knowledge into functional structures. The iterative nature of design, testing, and analysis fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills, crucial for effective engineering practice.

The enduring significance of bridges as critical infrastructure necessitates ongoing innovation and rigorous application of scientific principles. Future advancements in materials science, computational modeling, and construction techniques promise to further enhance bridge design and performance. Continued exploration of fundamental physics concepts, coupled with practical experience gained through projects such as these, remains essential for developing sustainable and resilient infrastructure solutions for the future. These endeavors not only contribute to societal progress but also deepen understanding of the physical world and its application to engineering challenges.